Aramco might ultimately import gas

Aramco might ultimately import gas

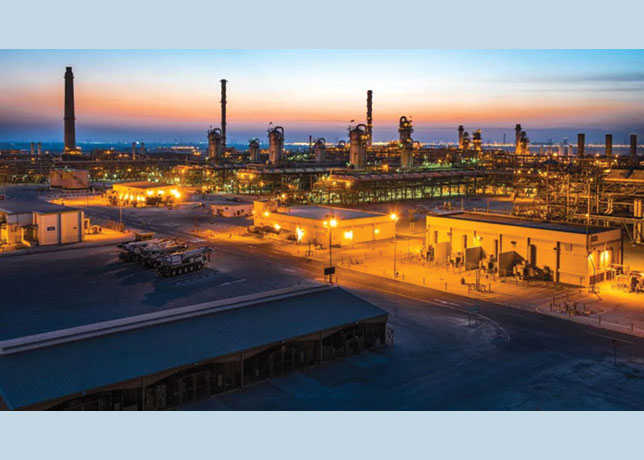

Industrial expansion will require much more gas – a commodity already in short supply amid struggles to supply households as well as industry. The shortages get worse during the hot summers when up to 900,000 barrels of oil have to be burned

The notion of natural gas imports was until recently out of the question for Saudi Arabia, which has for the past two decades attempted to meet soaring power demand by finding and developing its own reserves.

But as the kingdom’s new policymakers look to diversify the economy away from oil, what was once unthinkable has just become a lot more thinkable, with Saudi Arabia potentially swelling the ranks of Middle East LNG importers later this decade.

Launching his grand Vision 2030 in April, the country’s powerful deputy crown prince, Mohamed Bin Salman, set out ambitious objectives to wean Saudi Arabia off what he called its "addiction to oil" revenues and to create a bigger downstream industry to build up a stronger, higher value export chain.

But industrial expansion will require much more gas - a commodity already in short supply amid struggles to supply households as well as industry. The shortages get worse during the hot summers, when up to 900,000 barrels of oil have to be burned to meet surging electricity demand.

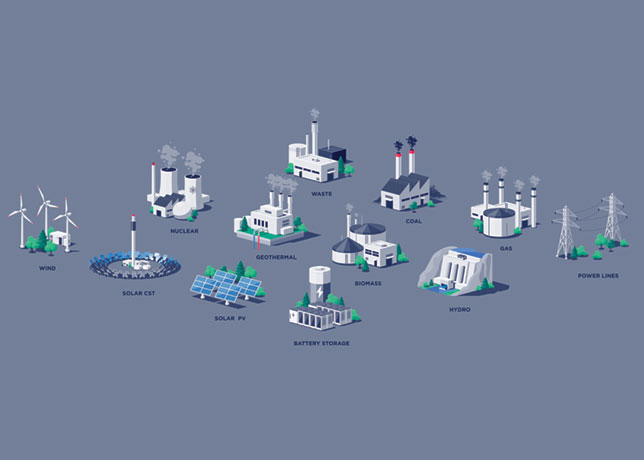

Fleshing out some of the details in a National Transformation Programme (NTP), energy minister Khalid Al Falih says one goal is to increase gas’ share of the energy mix to 70 per cent from 50 per cent today. He says the gas could either be domestic production or imports, but domestic gas would be preferable. Still, the very mention of imports represents a major change.

"They are taking a different approach now and they seem to be willing to import gas. I think it will most likely be in the form of LNG," says Ghassan Alakwaa, energy analyst at Saudi Arabia’s Apicorp. But he says that wouldn’t happen for a couple of years, at least. Other analysts agree that LNG looks likelier than piped gas, given tricky political relationships with major nearby gas producers Qatar and Iran. "The main problems I can see is that they don’t want to get it from Qatar or especially Iran, so presumably that means LNG," says Robin Mills, chief executive of Qamar Energy, a Gulf-based energy consultancy.

Industry is already paying more for gas, after Riyadh raised prices last December to $1.25 per million Btu from 75¢/mmBtu, so "technically and commercially it’s feasible enough," Mills says. The government has says it plans to phase out fuel subsidies over the next five years.

Saudi Arabia’s economic transformation will include an initial public offering in Saudi Aramco, the world’s biggest, lowest cost oil producer, in 2018. Ahead of the partial privatisation, Aramco sources say the company may consider investing in upstream projects overseas from which it could bring equity production back home, rather than rely solely on gas sourced from the spot market.

On the domestic front, Aramco has been tasked with doubling production from 12 billion cubic feet per day (124 billion cubic metres per year) today to around 23 bcfd over the next decade. A first phase would be to boost dry gas production capacity to 17.8 bcfd by 2020.

Contracting sources in the kingdom say all the contracts recently awarded by Aramco relate to gas projects, particularly updating the pipeline network. The sources say it let three contracts together worth $1 billion last December for the second-phase expansion of its master gas pipeline system, designed to improve fuel distribution.

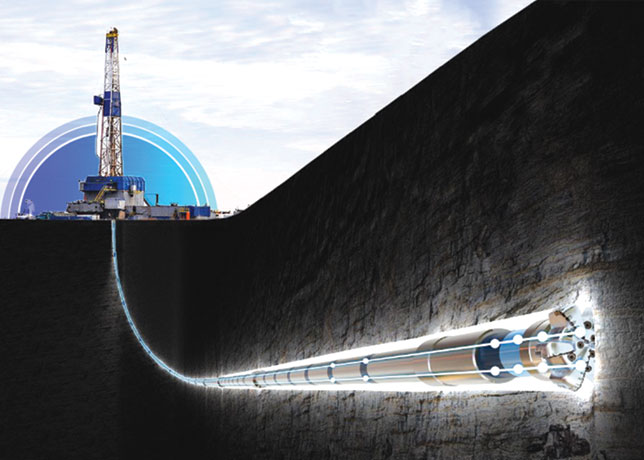

The plan did not specify the sources of incremental gas production, or say how much of the $75 billion first-phase NTP budget would be allocated to gas. Aramco is looking at both conventional and unconventional gas, shale as well as tight gas.

Falih told a media briefing in Vienna that shale exploration has gone "very well" in the south, east and north - although "in the northern area it’s not exactly shale, but unconventional gas."