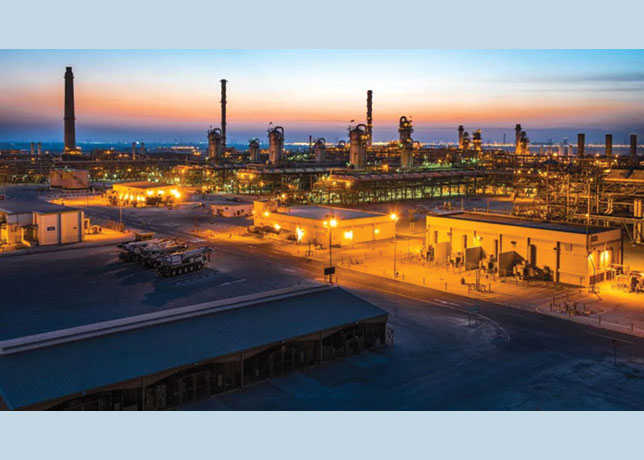

Lukoil evacuated some of its personnel from the West Qurna-2 field

Lukoil evacuated some of its personnel from the West Qurna-2 field

Social unrest in Iraq has threatened to disrupt operations at one of the country’s biggest producing oil fields, with Baghdad turning to its Gulf neighbours to help provide power supplies and defuse the ongoing crisis linked to poor public services, high unemployment and soaring temperatures, sources say.

Political paralysis and mounting anger have gripped Opec’s second-largest oil producer since elections in May, with power outages and a lack of clean drinking water triggering demonstrations in oil-rich Basra province in early July that quickly spread through Iraq’s southern cities, partly in response to a deadly police crackdown. Thousands marched through the streets of Baghdad.

The protests come as global oil markets contend with a host of supply disruption fears in countries like Venezuela, Iran and Libya.

Russia’s Lukoil on July 14 evacuated some of its personnel from the West Qurna-2 field, which produces around 400,000 barrels per day, after it was targeted by demonstrators in Basra. The unrest did not affect production there, or at BP’s 1.5 mbpd Rumaila field, Iraq’s largest, and nearly all of Lukoil’s personnel have now returned after the security situation improved.

But it was the first time Lukoil had to evacuate staff, and reflects the dangers posed by the current crisis. Similar protests erupted in 2015, when angry youths also took to the streets demanding jobs. But the Russian firm managed to defuse the unrest then, by negotiating with tribal chiefs. There have been no such negotiations this time, as Lukoil’s reduced staff levels in Iraq, after an investment freeze several years ago, mean it no longer has specialists capable of liaising with the local community.

A key issue for Lukoil, as for other IOCs operating in Iraq, is the number of Iraqis it employs. They now account for around 60 per cent of its staff, but Baghdad is under massive pressure to create local employment opportunities and wants this figure to rise to 80 per cent. The energy sector employs just 4 per cent of the Iraqi workforce, according to some estimates, despite oil revenues accounting for nearly 90 per cent of the government’s income last year.

Another issue that could hold up future investment at West Qurna-2 is getting the state-run Basra Oil Co. (BOC) to approve contracts. Lukoil is currently looking to award two major contracts — for new water injection facilities and a gas power plant — as part of its full development plan, to eventually raise production to 800,000 bpd. But competition for funds will be fierce, especially if the caretaker government of Haider Al Abadi allocates trillions of Iraqi dinars to Basra province, as promised, to improve local services — providing clean water, boosting power supplies and improving public healthcare, housing and schools. If BOC refuses to grant its approval, as it has in the past, Lukoil’s output targets could be seriously delayed.

Baghdad’s inability to pay its debts to Iran — and the surge in Iranian electricity demand — explain why Tehran cut off more than 1,000 megawatts of power supply earlier this month to Iraq’s southern provinces of Basra, Nassiriyah and Amara, aggravating the country’s severe power shortage, according to an official at Iraq’s Ministry of Electricity.

But he said this only accounted for around 12 per cent of Basra’s total power demand, and that others have stepped in to help cover the shortfall until Iranian power supplies resume. The Ministry of Electricity announced that Kuwait had agreed to supply Iraq with kerosene.