Luaibi ... persuading foreign companies to help the government raise output

Luaibi ... persuading foreign companies to help the government raise output

Lingering security concerns in former Islamic State strongholds, the breakdown in relations between Baghdad and Erbil, and pervasive corruption all threaten to undermine efforts to revamp Iraq’s vital oil and gas sector

Iraq's oil and gas infrastructure has taken a hammering since Islamic State swept into the country in 2014, with refineries destroyed, oil wells set ablaze, pipelines shut in and production facilities looted.

With Islamic State now all but defeated in Iraq, the government has moved swiftly to reaffirm control of territory and assets that it had lost to the jihadists—and to the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) -- in what could herald a new era in the country’s fortunes.

After retaking the oil fields in and around Kirkuk from the KRG, Iraqi security forces have recaptured the last Islamic State bastion of Al Qaim, near the Syrian border in Anbar province, and with it the nearby Akkas gas field. Now, Baghdad is pushing ahead with plans to renovate export facilities and boost output from fields back under its control.

But plenty of factors could complicate those plans. The full extent of the damage and the investment needed for repairs is not yet clear. Lingering security concerns in former Islamic State strongholds, the breakdown in relations between Baghdad and Erbil, and pervasive corruption all threaten to undermine efforts to revamp Iraq’s vital oil and gas sector.

Finally, the urgently-needed reconstruction of towns and cities destroyed in the war—including Mosul, Iraq’s second-largest city—will compete for the limited funds available. Below, are some of the recent achievements and looks at the challenges that lie ahead.

• Recaptured oil and gas fields: The vast majority of Iraq’s oil and gas fields, located in the far south, were beyond Islamic State’s reach. But small producing fields in the north generated important oil revenue streams for the jihadist group. They included the Ajil and Himrin fields in Salahuddin province, which Baghdad recaptured in September, and Qayara and Najma in neighboring Nineveh province, which Islamic State lost control of late last year.

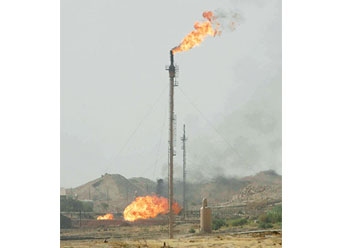

Some of these fields have significant potential. But the militants sabotaged many of them as they retreated, blowing up dozens of oil wells that have taken many months to extinguish. The jihadists set 18 wells ablaze at the Qayara field alone, according to a UN report. Production there has now resumed, reaching 7,000 barrels per day.

But this is a far cry from the original producvtion targets — even if inflated — of 120,000 bpd at Qayara and 110,000 bpd and Najma that Angola’s state Sonangol signed up to achieve in 2009 before exiting the acreage over security concerns in early 2014. Four wells are meanwhile still burning at the Allas and Ajil fields, where the surrounding area is mined. Ajil previously produced 25,000 bpd of crude and 150 million cubic feet per day of gas.

|

Four wells are burning at the Allas and Ajil fields |

Among Baghdad’s greatest challenges will be persuading foreign companies to help the government raise output from fields that slipped out of its control during the war against Islamic State.

These include fields seized in 2014 by Kurdish forces in response to the Iraqi army’s collapse—notably Kirkuk, where the ministry hopes to enlist BP’s assistance in hiking production to more than 700,000 bpd, and Nineveh’s Ain Zalah, which state North Oil Co (NOC) is working to bring back on stream.

Development work was abandoned at the nonproducing Akkas and Mansuriya gas fields, operated by Korea Gas Corp. and Turkey’s TPAO, respectively, when they were overrun by militants three years ago. Akkas was targeting output of 400 mmcfd and Mansuriyah another 320 mmcfd. "We have asked companies working in those two fields to resume work," says Oil Minister Jabbar Al Luaibi.

But security concerns are not the only deterrent. The technical-service contracts currently on offer in Iraq have proven highly unpopular with international firms, prompting some to relinquish their acreage. A Basrah Oil Co. official says that Royal Dutch Shell will exit the giant Majnoon field by June.

• Crude export pipelines: Rehabilitating the export pipeline network linking Kirkuk directly with Turkey is a top priority for the Iraqi government as it seeks to bypass the KRG. Al Luaibi says the Turkish energy ministry has agreed to help fix the Iraqi section of the pipeline, and work could be completed in the next six months. But it could take much longer, given the damage to pipelines and pumping stations, some of which were completely destroyed by Islamic state, according to Iraqi officials. The export line also runs through Baiji, where fighting between jihadists and Iraqi security forces severely damaged the refinery there.

Al Luaibi states that Iraq’s state oil marketer Somo is "the only entity authorized to manage the marketing of crude oil through the port of Ceyhan," an instruction clearly aimed at cutting off KRG exports from the Turkish port. Iraq’s northern export pipeline—its largest—has a nameplate capacity of 1.6 mbpd but was pumping a maximum of 400,000 bpd when it was closed in 2014.

Illustrating the urgency of reopening it, NOC has taken the drastic step of shutting in the Bai Hassan and Avana oil fields in Kirkuk, which were together producing 275,000 bpd, or around half of the KRG’s crude exports before the crisis, to avoid exporting crude via the Kurdistan region.

Until the northern pipeline is reopened, Iraq’s only viable outlet is through the southern Basrah terminal. Southern export capacity was raised to 4.6 mbpd, Al Luaibi says, with the commissioning of a new single point mooring buoy. But pipeline, storage and pumping constraints are all contributing to bottlenecks there.

Alternative export routes, including the 1.6 mbpd Iraqi Pipeline in Saudi Arabia (Ipsa) that was closed in 1990 and the planned 1 mbpd of pipeline linking Basrah to Jordan’s Red Sea port of Aqaba, are getting some attention—Ipsa after improved ties between Baghdad and Riyadh. But both still look a distant prospect. Any Jordan pipe, for example, would have to transit Anbar province, formerly an Islamic State stronghold.

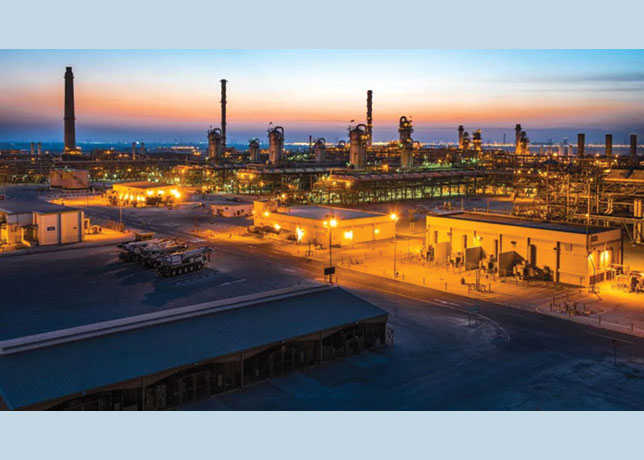

• Refining sector: Baiji, once Iraq’s largest refinery with a nameplate capacity of 310,000 bpd, has been out of action since late 2014 and needs rebuilding. The ministry plans to install a new 70,000 bpd unit that could be operational in six months. Some progress has been made at smaller refineries: The 16,000 bpd Haditha refinery in Anbar province restarted a month ago; the 30,000 bpd Siniyah refinery in Salahuddin province is expected to start operating within days; and the the 20,000 bpd Qayara refinery has been reopened after it was severely damaged.

But Iraq’s refining sector suffers wider ills. The Doura refinery in Baghdad is currently operating at a rate of around 80,000 bpd, just 40 per cent of its nameplate capacity, and some of the contracts awarded in recent years have yielded little, as with the $6 billion contract, won by a little-known Swiss firm called Satarem in 2013, to build a new 150,000 bpd plant in Maysan province. Work has yet to begin, Iraqi officials say, and the government is now threatening to cancel the licence and re-tender the project.