Rosneft ... signing accord with KRG

Rosneft ... signing accord with KRG

The progress also points to Russia’s growing involvement in Iraq, limited engagement by Western powers and Washington’s haphazard regional foreign policy in particular, has created opportunities for others to take strategic positions

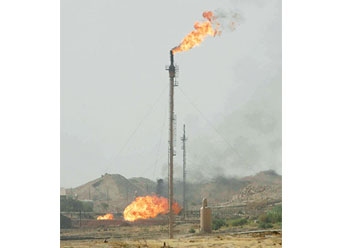

In accord signed by Russia’s state-backed Rosneft and the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) in St. Petersburg on developing Kurdish gas supplies was thin on detail, but it served as a reminder that the big energy cooperation deals they struck last year remain on track.

The progress also points to Russia’s growing involvement in Iraq, where, as in Syria beforehand, limited engagement by Western powers and Washington’s haphazard regional foreign policy in particular, has created opportunities for others to take strategic positions—including, in Iraq’s case, Chinese oil firms.

For Iraq, this shift comes at a time of deepening political limbo and uncertainty: Talks on forming the next coalition government after the May 12 parliamentary election could take months, and parliament’s decision to carry out a manual vote recount after widespread allegations of fraud has heightened tensions, although it is unlikely to change the overall result.

Moscow was Iraq’s only major ally not to oppose the KRG’s independence referendum last year, and it appears to be paying dividends in terms of both energy deals and political leverage. The St. Petersburg accord, signed by Rosneft boss Igor Sechin and KRG Natural Resource Minister Ashti Hawrami, envisages carrying out preliminary work for gas pipeline infrastructure that could eventually allow Erbil to export gas to Turkey and beyond.

But at the signing ceremony, Rosneft also revealed plans to start a pilot oil production project under one of its production-sharing agreements with the KRG, with initial output of 3,500-5,000 barrels per day. Small volumes, but Kurdish sources say they will come from the Ain Zalah field, which lies in Iraq’s Nineveh province outside of official KRG territory, making the plan highly controversial.

Baghdad was clearly irked by the deal, which it branded illegal, but is in no position to retaliate. Russian oil firms Gazprom Neft, Lukoil and Rosneft have a substantial presence in southern Iraq. Lukoil finalised changes to its contract at the 400,000 bpd West Qurna-2 field last month, where it plans to spend $4.5 billion and double output by 2025. Rosneft, which recently announced a discovery on Block 12, has even been talking with BP about teaming up, potentially at Kirkuk.

Western diplomatic engagement in Iraq revived dramatically after Islamic State’s advances in 2014 but has been in retreat since Baghdad declared victory over the jihadist group last year. At the same time, the US government’s main regional preoccupation—withdrawing from the nuclear deal with Iran and reimposing sanctions—has drawn sharp criticism from Baghdad.

Brett McGurk, the US special envoy to the anti-Islamic State coalition, has held talks with political leaders in the Iraqi capital since the elections but no longer has the full weight of Washington behind him. Russia, meanwhile, is emerging not just as one of the biggest investors in the oil sector, but also as a major weapons supplier to Iraq, although Baghdad’s potential purchase of Russia’s S-400 missile defense system puts it at risk of being targeted by US sanctions.

"You could make the case that there’s a very well-considered, strategic agenda here, at a time when Western countries are simply not being strategic in how they are acting," says Gareth Stansfield of the UK’s Exeter University.

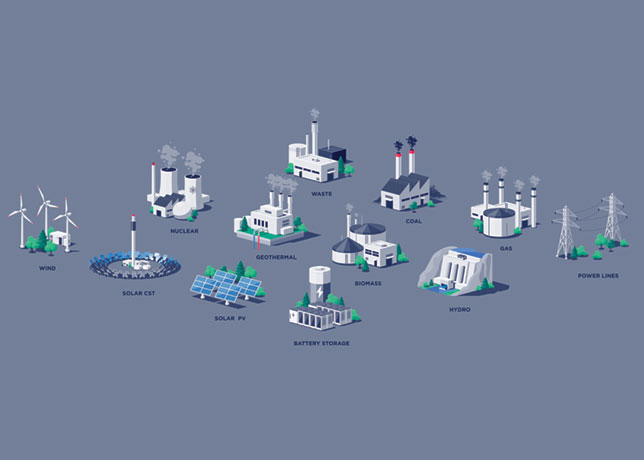

This political shift takes place as many Western firms are gradually losing interest in Iraq’s vital oil sector, despite its vast, low-cost reserves, but with Asian firms motivated by future supply concerns willing to accept the razor-thin margins on offer. None of the Western majors except Eni participated in Iraq’s fifth upstream bid round.