It’s been an extremely weak start to the new decade for liquefied natural gas (LNG) with spot prices in Asia falling to more than 10-year lows, but it’s not all doom and gloom for an industry that sees itself as part of the solution to climate change.

At below $4 per million British thermal units (mmBtu), LNG is at the weakest level since summer of 2009, according to data from S&P Global Platts.

To put the current price in perspective it’s worth noting that the winter peak for 2018/19 was $10.90 per mmBtu and $11.50 a year earlier, while the record high is $20.50 from the winter of 2013/14.

A combination of factors is working to drive prices lower, both structural and temporary. The temporary factor is that milder winter has crimped demand for heating, and thus for LNG, in top importers Japan, China and South Korea.

The structural factor is that the LNG market is now well-supplied given the completion of the last of eight new projects in Australia and the commissioning last year of four in the US.

A further 17 million tonnes of annual LNG capacity is expected to be commissioned this year in the US, and beyond this year there will be new supplies from Canada, Qatar, Mozambique and Nigeria among others.

The glut of LNG is both good and bad news for producers. It will obviously hurt the economics of new projects and lead to longer pay-back times on investment.

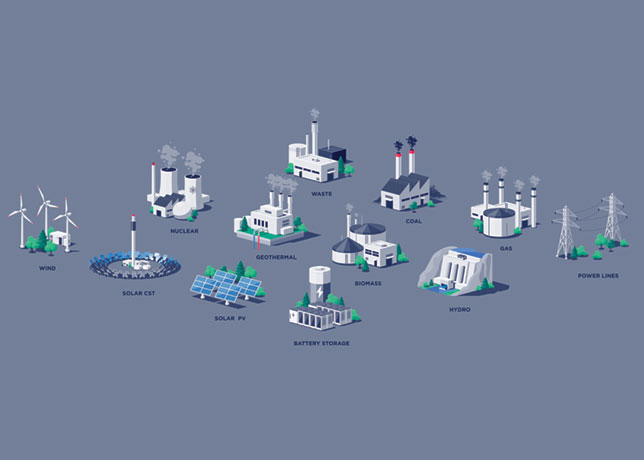

However, it will also help to make LNG a more competitive fuel, especially in Asia, where it faces a struggle against both coal and renewables.

LNG was once described by an executive at an Indian power utility as the "champagne of fuels", in that it was cleaner than coal and just as reliable, but too expensive.

However, the dynamics are changing. The economics of building and operating a natural gas plant using imported LNG are likely to prove competitive against doing the same with imported coal. The factors that are all swinging in favour of LNG include the cost of construction of an LNG import terminal and the gas-fired plant, which is well below the cost of building an import terminal for coal and a new power plant. Thus several Asian countries that had been considering new coal-fired plants are now assessing gas-fired units.

The argument for LNG becomes more favourable if climate change and environmental factors come into play, especially if developed nations, such as those belonging to the European Union, do go ahead with plans for carbon-adjustment tariffs.

Of course, LNG also faces a threat from the rapid lowering of the price of renewables such as wind and solar, but it is here that cheaper LNG prices may ultimately work in the industry’s favour.

If more Asian countries and utilities sign up to building LNG import facilities and gas-fired power generation, as well as switching to natural gas for industry and households, it will give the LNG industry a client base that will be hard to lose.

With new coal mines and power plants increasingly finding it hard to access capital and insurance, the low price of LNG offers the industry an opportunity to seize, and maintain, market share.